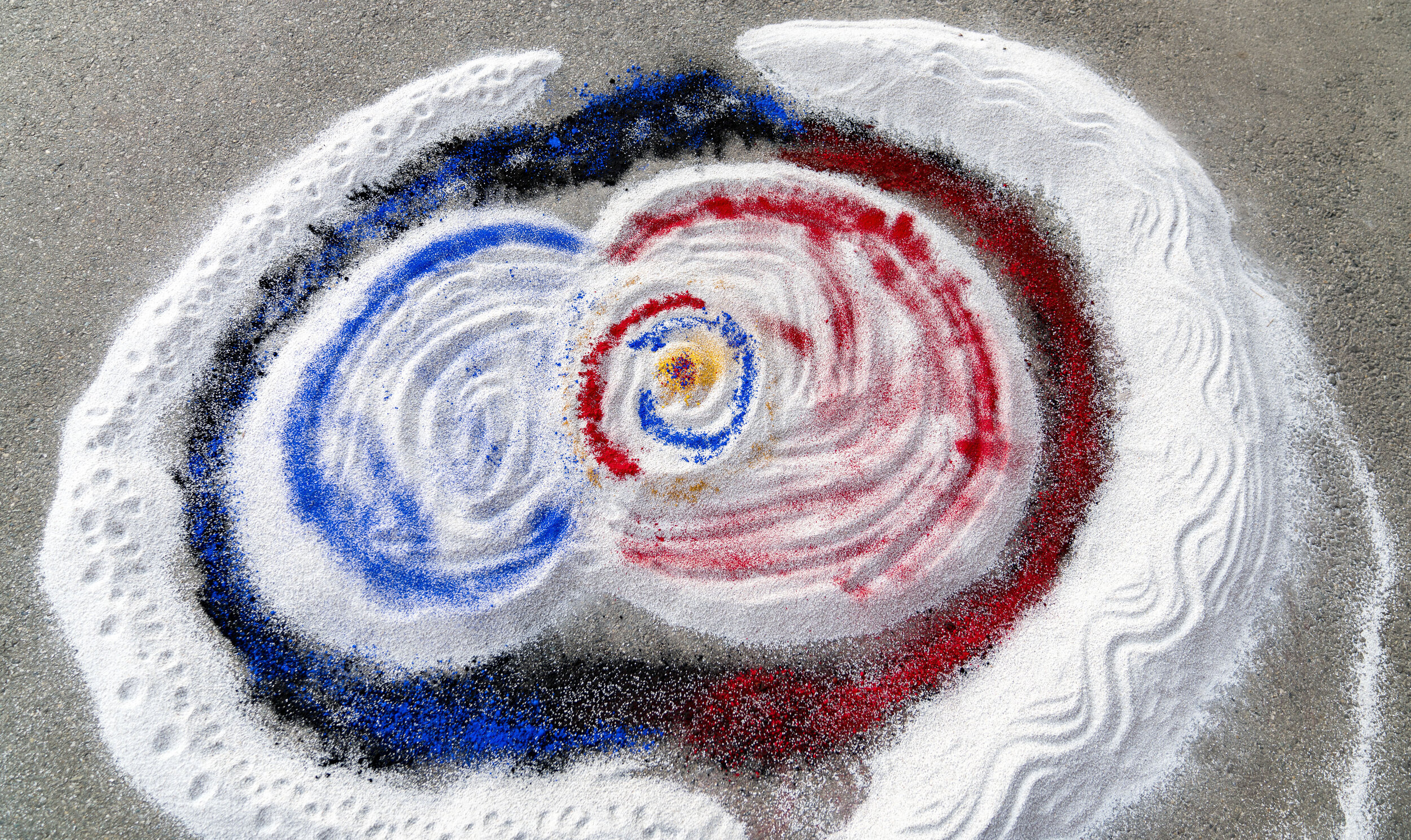

Colours, 2017, performance/mixed media Ph. Pino dell’Aquila

IN-BETWEEN

A conversation with Tommaso Tosco

by Elena Inchingolo

Simplicity is not an objective in art, but one achieves simplicity despite one’s self by entering into the real sense of things. Simplicity is complexity resolved: you have to feed yourself on its essence to understand its value.Costantin Brancusi

EI: Tommaso, you were born in 1957 in Santena, Turin, where you still live and work. However, in the late 1970s, after your graduation, you moved to Torino, approaching the world of ceramics as an autodidact. In which cultural framework did you start working as an artist?

TT: In those years, I attended a few classes to learn the art of ceramics, getting in touch with ceramists and internationally renowned artists, such as Umberto Ghersi from Albisola – an already indispensable assistant of Lucio Fontana – and Nanni Valentini, a generous man and an outstanding artist. Between 1980 and 1990, I had the chance to work with some ceramic factories in the area, such as Laria Klinker in Santena and Klinker Sire in Marene, beginning to practice with clinker and other materials, like lava and metals.

This research on the matter thus led me to sculpture and to the big installations that offered me the opportunity of entering some fruitful collaborations with some galleries of contemporary art in Torino, like Galleria Martano, which was already following Nanni Valentini’s work, and Galleria Luisella D’Alessandro.

In the late 1980s, though, I chose to withdraw from the art system for personal reasons, yet keeping to independently process ceramics and metals, in a suspended time that allowed me to travel in spirit.

EI: Today, after quite some while, you have conceived an anthological exhibition, that may be representative of your artistic journey. How did this idea come to life?

TT: Some time ago, I exhumed among my records some photographs shot in 1985 by Franco Mello, with whom I have had a long-standing relationship of deep friendship, at the Klinker Sire plants in Marene. Since then, I have felt the urge of venturing again into the design and creation of big shapes, but using weathering steel, for this material’s hardiness and its chromatic variance when exposed to the environment. A new challenge that enriched me with new expressive lymph.

EI: How did your passion for ceramics come to life?

TT: As is often the case, my love for the earth occurred by chance, but it soon became a great passion.

EI: Forging the earth means meditation and demiurgic force at the same time. Which are the features of this material that attract you most?

TT: To me, forging the earth means to feel within the becoming of things. It means designing and waiting for the outcome in an ever-changing and unrelenting space-time dimension, starting from the type of material that I use and the working context in which I place myself.

EI: From your work in ceramics in the 1980s to the most recent accomplishments in weathering steel with silvery insertions and welds, achieved in collaboration with goldsmith MauroBonafede, a strong urge of reconciling inner energies, duality and opposed forces neatly emerges. In your works, one senses a deep bond with the great contemporary sculpture, from Constantin Brancusi for your formal essentiality to Richard Serra for your expressive thoroughness, to Richard Long for your compositional fluency with a naturalistic allegiance. Your sculpture has an elemental structural logic, which - for this very reason - enables multiple moves and crossings, both physically and mentally. Notably, in the Slit series, the tearing at the heart of the work, from which the title derives, conjures up naturalistic crevices, the cracking of the earth and thunderbolts from thesky, and some deep dichotomies in the soul. How did this last work come to life?

Colours, 2017, performance/mixed media Ph. Pino dell’Aquila

TT: Various and diverse were my sources of inspiration in response to an inner vibration of my own. Surely, Mark Rothko’s great retrospective exhibition at the Kunsthalle in Hamburg in 2008 and the brilliant debate between Richard Serra and Costantin Brancusi at the Basel Foundation in 2011; Lucinda Childs’s and the Momix group’s dance; the cracking of the earth in Iceland; the ice crevices in Antarctica; the sacrality of the Indian sexual forms; and most of all, Morton Feldman’s essay, “Vertical Thoughts”. In 2013 I caught those suggestions and imagined, with Franco Mello and Mauro Bonafede, the creation of some sculpture- jewelry in weathering steel, which then became part of Sfioro collection, together with the works of Michelangelo Pistoletto, Emilio Isgrò, Marco Gastini, and Mimmo Paladino. The sculpture-jewelry has been for me a sort of prototype, from which my sculptural series Slit took shape.

EI: Who did influence your creative afflatus in painting?

TT: I always look at painting as if it was sculpture. In this sense, I believe that Mark Rothko’s painting is the closest to my feeling. The colours of his canvases seem to come out from the picture and to flutter in space. The gestural expressiveness of the matter in Emilio Vedova’s work and in his large canvases also elicits in me strong emotions. EI: Thinking of Brancusi’s work, it originates from rhythm, the very essence of language and thought. Likewise, music is a primary element in your artistic research: John Cage’s “musicality of silence” and Morton Feldman’s experimental compositions – such as Rothko Chapel (1971) – are the soundtrack of your art-making process. Has it always been like that?

TT: Music has always affected my work in a meaningful way. I love every musical expression, from the well-tempered cembalo of Bach to Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Mantras, from John Cage’s Landscapes to the new wave sonorities of Talking Heads and the Japanese drum players, from the American Minimalism of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich and Philip Glass to Alva Noto’s noise-music essays. Take me to the river (1986), made up of approximately 30 elements in terracotta and Luserna stone is a tribute to the homonymous piece by Talking Heads, who in those years used to accompany my days. Contemporary dance, meant as sculpture in movement, is another great passion of mine. A meaningful example is my work called Underwood that I accomplished in 1988, in terracotta, being inspired by the famous homonymous performance, dated 1982, of the American dancer and choreographer Carolyn Carlson, one of the highest and most original expressions in the international dancing scene.

EI: Even today, John Cage’s remarks about silence are trulymodern as an inspiration for a new vision of life and art andas an opportunity for a new relationship between nature and culture. Actually, silence is meant as an “apparent vacuum”, i.e. full of sounds, a resonant silence, that triggers new perceptive powers, both ethical and aesthetical. In order to achieve his most famous silent work, 4’33” (1952), Cage relied on the steady dialog with the entourage of his fellow artists, such as Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Philip Guston: this gave birth in New York, in the early 1950s, to a new positive concept of vacuum between music and painting.

The encounter of art and music transformed the audience’s listening habits thoroughly: if listened to, each sound from the real environment deserves to become true music. In sculpture, one can look at and sense the surrounding reality through the work of art and its compositional counterpoints: the slits, the crevices, the grids, the holes on the matter. What is your point of view with respect to this concept?

TT: I regard silence as a plastic dimension that has to be made visible through the act of fruition, in a suspended time.

EI: What do you mean by “suspended time”?

TT: Along the years, during my frequent trips to Northern Europe, I often sensed this “suspended time” in the expressions of wildlife, namely the absolute feeling of losing one’s bearings in time. I felt this emotion in the northern colours, so rarefied and at the same time so violent as to bewilder the sight and delete the skyline. It is as if everything was there today, just like it was there yesterday and it will be there forever, endlessly.

Colours, 2017, performance/mixed media Ph. Pino dell’Aquila

EI: Red is your colour, a symbol for passion, representing fire, energy, action. You use fire as an instrument to make the demiurgic act in the ceramic creation an ultimate step and to tear and penetrate the metal, giving it new life. It is two moments of your artistic journey melting together seamlessly.

What would you like to convey to the people who enjoy your sculptures?

TT: I would like to convey the feeling of “beyond”, of “possibility”. I would like to shake up the “inner labyrinths” and cross the “suspended thoughts” that each of us intimately conceals, with our own tearing, cracks and scars.

EI: In your work, one feels the purpose of giving relevance to the installation’s compositional meaning in a dialogic confrontation with the space and the viewer’s perception. On show, you are offering again the installation called Rebis o Due Soli (Rebis or Two Suns), reinterpreting the compositional and formal process of this work dating from 1987, which included two round, suspended, elements in metal, a mandala in coloured silica and a wall painting. Thus, two moments of your artistic journey get confronted. Past and present join in towards a new dimension. What do you expect from the future?

TT: In the future, I would like to be able, now and ever, to have aserene and all-embracing look at innovation. I have almost completed the Slit series, and I would like to start on a new cycle of works devoted to the idea and the meaning of torsion.